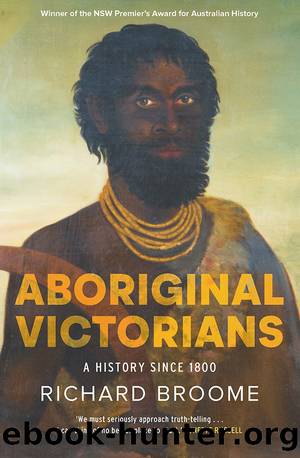

Aboriginal Victorians by Richard Broome

Author:Richard Broome

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Allen & Unwin

Published: 2024-01-30T00:00:00+00:00

Framlingham youths, 1944. Back row, LâR: Walter Austin, Sid Austin, Henry Alberts. Front row, LâR: Roy Rose (father of Lionel), Chris Austin. (Courtesy Amy and Robert Lowe, Warrnambool)

The Framlingham community battles evictions

By 1950, 86 people resided in 14 houses at Framlingham, 38 of them children, most taught by John Sharp at the reserve school. Noel Couzens and his brothers, sons of Nicholas Couzens, now share-farming at Panmure, rode their bikes ten kilometres each way to attend the Framlingham School. The school was a vital link that Aboriginal people off the reserve maintained with the âFramâ community. Community was also sustained by the Mathiesons who conducted religious services there until 1954. The reserveâs families were sustained by the menâs contract wood-cutting for the Forestry Commission, basket-making by the women, and pension and child endowment payments. Several white female activists who visited in 1950 thought âthe women at Framlingham seemed abler than the menâ.51

A new crisis arose at âFramâ in late 1949. Doris Austin and her three children, moved into a vacant reserve house from a hut in the forest, but were ordered off by Constable Rowe. Austinâs brother and aunt wrote to the Board asking: âAre they to camp in hollow logs and carry their swags about with their children behind them?â52 A similar thing happened in August 1950. Peter and Phyllis Dunnolly and family, who had left to work in another district, returned after six months and paid £9 rental owing. Dunnolly then requested that his sister-in-law, Ella Austin, and her five children be allowed to live in their house. This was denied. Phyllis wrote to her aunt Mary Clarke and asked her to seek help from Doris Blackburn, President of the Womenâs International League for Peace and Freedom, to stop them ârobbing us poor black people, they took our pines [trees] away and one house and now they want to take anotherâ. In a second letter Phyllis claimed Constable Rowe had refused a further rent payment, saying the house was to be sold, and again appealed for her aunt to seek help.53

A Womenâs International League for Peace and Freedom deputation assisted by Helen Baillie, a white activist, gathered facts at Framlingham and lobbied the government. The Board and Chief Secretary denied there would be any evictions, but stated the Framlingham houses were built for emergency accommodation in the Depression and were never to be transferred. They were to be sold when the original occupiers left or fell behind in their rent.54 The Dunnolly house was sold and Ella Austin and family faced eviction. A public outcry forced a Board back-down in December 1950. A public meeting was sponsored by the League in February 1951 at the Australian Church in Melbourne, at which white women activists for Aboriginal people spoke, notably Helen Baillie, Cora Gilsenan and Anna Vroland.

Mary Clarke of Framlingham, a granddaughter of Louisa Briggs and thus a descendant of Tasmanian Aboriginal people (but not Truganiniâs great-grand-daughter as she claimed), also spoke.55 This was a supreme effort for her,

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Memory Code by Lynne Kelly(2401)

Schindler's Ark by Thomas Keneally(1884)

Kings Cross by Louis Nowra(1796)

Burke and Wills: The triumph and tragedy of Australia's most famous explorers by Peter Fitzsimons(1426)

The Falklands War by Martin Middlebrook(1383)

1914 by Paul Ham(1345)

Code Breakers by Craig Collie(1252)

A Farewell to Ice: A Report from the Arctic by Peter Wadhams(1248)

Paradise in Chains by Diana Preston(1247)

Burke and Wills by Peter FitzSimons(1237)

Watkin Tench's 1788 by Flannery Tim; Tench Watkin;(1232)

The Secret Cold War by John Blaxland(1213)

The Protest Years by John Blaxland(1205)

THE LUMINARIES by Eleanor Catton(1194)

30 Days in Sydney by Peter Carey(1160)

Lucky 666 by Bob Drury & Tom Clavin(1155)

The Lucky Country by Donald Horne(1140)

The Land Before Avocado by Richard Glover(1118)

Not Just Black and White by Lesley Williams(1085)